By UNISON’s assistant national officer for community, Haifa Rashed

I often get asked, what is the community service group? It seems a simple question, but even as an officer in the sector, it’s not simple to answer.

I can tell you who we represent. UNISON has 85,000 members in community, they are: housing officers, care workers, support workers, admin workers, project workers, children’s services workers and more.

I can tell you who those members work for. They work for charities large and small, non-profits and housing associations.

I can even tell you where they work. They can work in people’s homes offering frontline support and care, in women’s refuges, in LGBT+ spaces, in leisure centres or in offices like any other sector.

But when you look at the community service group as a whole, it’s hard to sum it up in one sentence and say – this is who we are. It may seem a bit of an academic exercise, but it has real consequences and tells us a lot about the issues community members face.

The range of roles, employers and workplaces make it a real challenge organising and representing members in the sector. There is no unifying pay structure and no national terms and conditions.

Moreover, many community members in UNISON sit within local government and health branches and this can have an isolating effect on them.

All of this makes it harder for workers in the sector to demonstrate their collective strength.

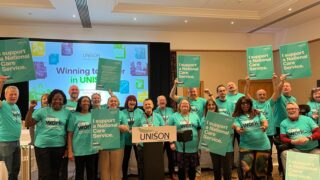

In turn, it makes the sector’s conference and seminar all the more important. Today (Friday), hundreds of community members will gather in Chester, debate issues workers are facing and find that common ground which they share.

Key among these issues is funding. Recent research from the National Council for Voluntary Organisations surveyed over 600 charity leaders across the UK. It demonstrated the reliance of the public sector on charities and non-profit organisations and highlighted some stark truths.

The voluntary sector delivers over £11bn worth of public services every year but 87% of organisations surveyed subsidise public service contracts and grants from their own funds to carry out services.

Four in ten said the funding they are awarded in grants and contracts has never covered their true costs, while 44% said they have not covered their costs since 2020 (at least).

For members, insufficient funding means charities struggle to meet their minimum wage and living wage obligations, or they have to find savings elsewhere. This can be by charging workers to pay for essential DBS and other criminal records checks, or by reducing training opportunities or employer pension contributions. It also translates to stagnant wages, with the sector falling behind both private and public sector rises.

Inevitably, less attractive wages, worse terms and conditions and more pressure to deliver increasingly extensive public services with less real-terms funding leads to issues in recruiting and retaining staff. And without strong recruitment and retention, workers are asked to cover even more and to stretch even further.

In housing associations, this means dealing with people with complex mental health issues and effectively acting as a one-stop-public-service-shop – housing officer, social worker, benefits adviser and more. It’s little surprise that there is an increasing turnover rate in the sector, particularly in customer facing roles.

Meanwhile in social care, a sector with over 150,000 vacancies, the recent government decision to limit migrant workers bringing dependents will do nothing but worsen the vacancy crisis. This is low-wage work which is hard enough.

The decision will make it all the harder and leave members who work on the social care visa at risk of being ‘tied’ to their employers and vulnerable to unfair employment practices.

There is common ground among members in the sector through the issues that they face.

Yet, when I’m asked what the community service group is, I don’t say it’s a group of people united by facing the same set of issues – but by something more fundamental.

They aren’t working for private profits for shareholders, or to bring political glory to politicians – whatever their employer, workplace or role – they are all providing support for people who need it, and they take great pride in the positive impact of their work.