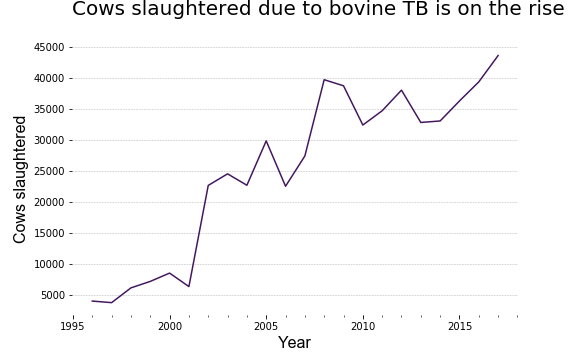

New data shows bovine TB is on the rise in England, proving that independent meat inspectors are needed more than ever.

The government has just published data showing 4,288 cows had to be slaughtered because of TB in March this year, up from the 3,900 in February, and continuing the general upward trend.

Since 1996 – when the data goes back to – there has been a massive 980% increase in cows slaughtered because of TB.

The disease is on the rise in England and Wales, but not in Scotland, which is considered ‘bovine TB free.’ But why does bovine TB matter?

It is possible for humans to catch TB if they consume unpasteurised milk or dairy products from an infected cow. According to the government website the risk of infection is “very low,” though a recent trend in unpasteurised milk is causing some to worry that the disease could pass more easily to humans.

Where bovine TB is having a big impact is on our economy. Slaughtering cows costs farmers time and money, and because the government compensates farmers when they have to kill their stock, it also costs the taxpayer.

The average number of cows slaughtered because of TB each month in 1996 was 336, while the average so far in 2018 is 4,094 per month. That means the average in 2018 is 12 times the average in 1996.

In 2017, there were 43,564 cows slaughtered because of TB, and so far this year there has already been 12,284 slaughtered. This huge rise is worrying, and according to the government no one is quite sure why it has happened.

In 2013, the government launched a long-term strategy to reduce bovine TB, and on the front line of that strategy are UNISON members.

Our members are independent meat inspectors for the Food Standards Authority (FSA), the organisation responsible for identifying contaminated meat. After an ‘on farm TB test’ has been carried out, if any cows have been identified as possibly having TB, then our members go in an inspect and sample the animals.

If any cattle do react, they’re taken to abattoirs where our members take samples and send them for analysis to confirm if the herd has bovine TB.

It is a hands-on job that many people would not want to do. As one member told us, “bovine TB lesions are yellow in colour and… can feel almost gritty when a knife is passed through the affected tissue.”

It is essential that trained, experienced people undertake this inspection as it involves differentiating between abscesses and lesions caused by other things.

The rise in TB is just one of the many reasons the government should increase the number of independent meat inspectors, not decrease them. In a recent report published by UNISON, 96% of meat inspectors thought that staff directly employed by the meat industry couldn’t be trusted to recognise and remove diseased sections of meat.

For more data stories about public services and the people who work in them visit UNISON’s public service data blog.